Jewish End of Life Practices - Jewish Guidance for the Moments Around Death

By: Rabbi Eva Sax-Bolder, Community Rabbi Boulder, CO

Pending Death to Just After Death

Courtesy of Kavod V’Nichun www.kavodvnichum.org

The Vidui

When death is imminent, it is appropriate to include the vidui (“confession”) prayer in support of the dying person (goses).

Alison Jordan, RN, MS, MFT, writes, “The Vidui provides an opportunity to unburden a heavy heart, return to a sense of hope for wholeness, and to let go of life peacefully. I continue to study the notion of death as atonement. In the meantime death is seen as a natural and G-d given experience to be encountered and met, hopefully in the comforting presence of others. Wholeness of healing is understood not in physical terms, but as redeeming acceptance, reconciliation, and peace.”

Alison Jordan has defined vidui as a prayer of confession to G-d. The deathbed confessional is said by or for the goses (dying person), but another type of vidui may be recited by others when addressing G-d concerning the relationship to the goses.”

“The traditional function of the vidui at the end of life is to provide words for the person who is in the process of dying. Our tradition is remarkably silent concerning those who are standing by the bedside. ”

If possible, the last words recited in the presence of the dying person should be the Sh’ma.

Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. Blessed is the Name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever. (Repeat 3 times)

The Lord, He is God. (Repeat 7 times).

The Lord is King, the Lord was King, the Lord will be King forever and ever.

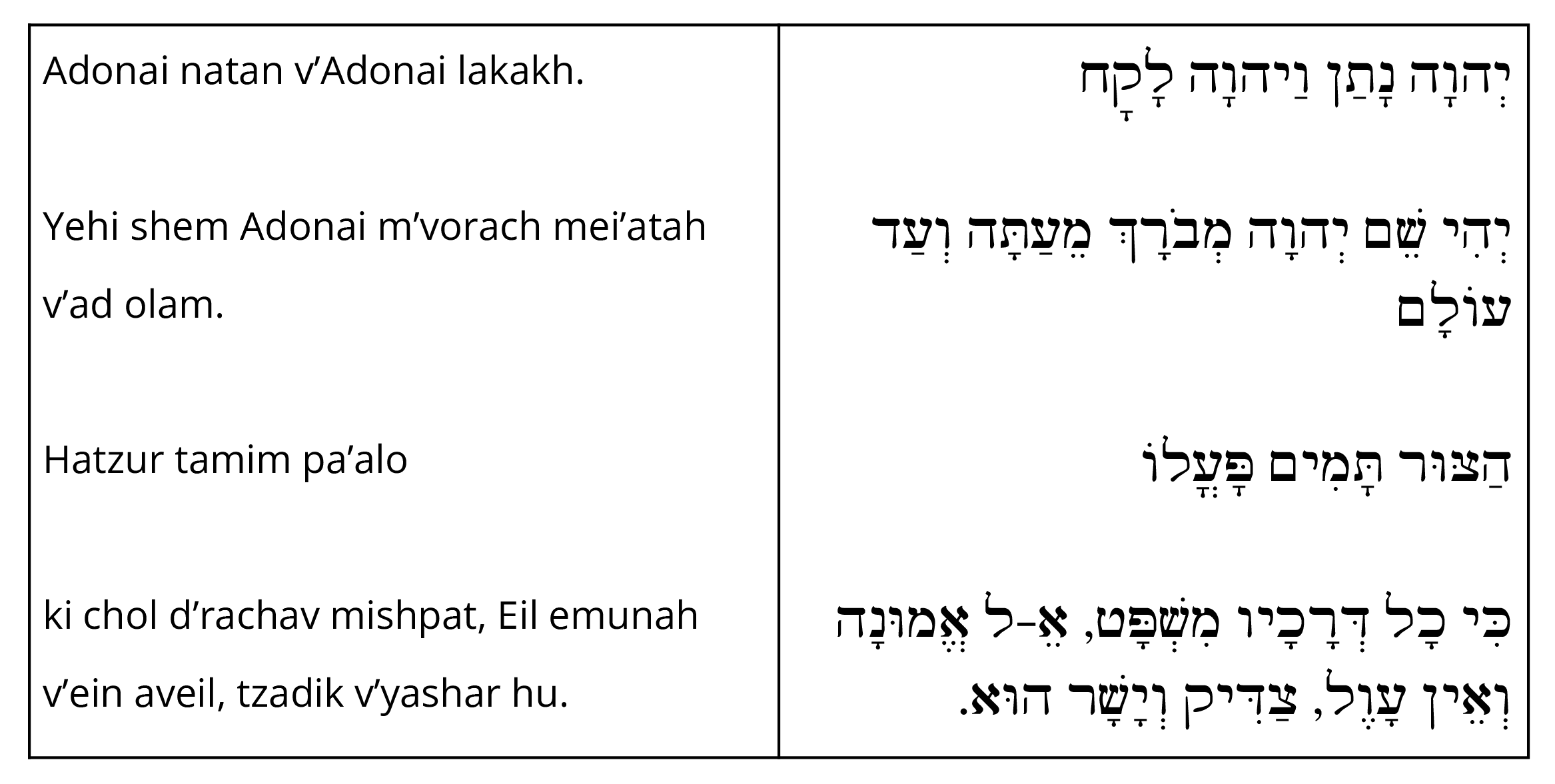

At the moment of death, those present should say the following:

Adonai has given, and Adonai has taken away.

Blessed is the Name of Adonai from now and forever.

The Rock, perfect is God’s work, for all God’s paths are just; God of faith without iniquity, righteous and fair is God.

Immediate Steps to Take

Jewish law defines a “primary mourner” as a parent, sibling, child, or spouse of the deceased. Traditionally, all primary mourners who are present at the moment of death perform the ritual of kri’ah (tearing of a garment) at this point, and continue to wear the torn clothing as mourners. Others who are present in the room at the moment of death also perform the ritual of kri’ah, even if they will not be mourners. This could include physicians, nurses, caretakers, visiting friends, relatives, or others.

Primary mourners who are not present traditionally perform kri’ah either when they first learn of the death or at the time of the funeral service. (The common current practice is for primary mourners also to perform kri’ah at the funeral.)

It is understood that those in the room have been present and have witnessed the moment of transition, and, therefore, have had a direct experience of being in the presence of death. It is customary that those who visit a cemetery wash their hands upon leaving the cemetery because they have been in the presence of death; all the more so for those who witness the actual moment of death. Even the death of a stranger is understood to affect a person, and being a witness to the death is understood to leave the observer vulnerable, at least for a short time. Kri’ah marks that vulnerability.

Other customs include:

Closing the eyes and mouth of the deceased.

Straightening the limbs.

Covering the deceased, often with a sheet.

Placing a candle near the head of the deceased.

Opening the windows in the room (if weather is problematic, windows are opened briefly, then closed again).

Covering the mirrors at home (this does not apply in a hospital or other facility).